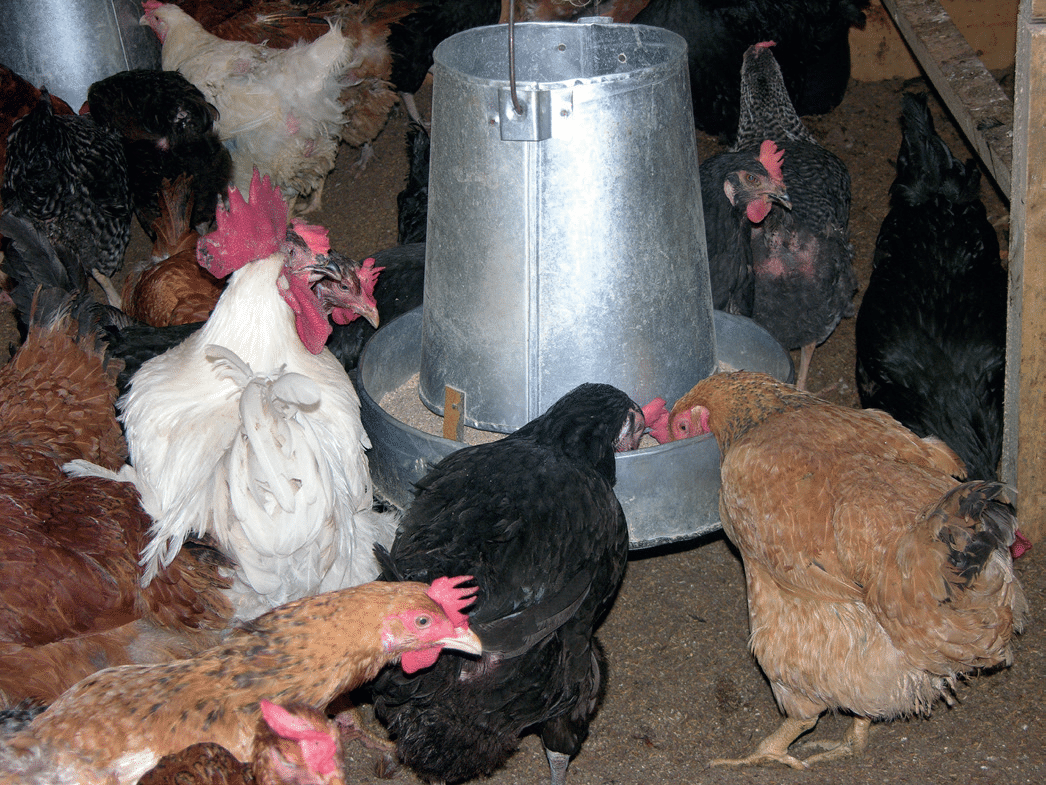

Kuroiler chicken farming

Mrs Teresia Ng’ang’ sells to her latest customer a batch of her day-old chicks , then makes her way back to the coop where she had been preparing feed for her other birds. Usually, Mrs Ng’ang’a, 44, imports and sells day-old Kuroiler chicks to mother units, a network of women farmers, who then resell them to households to improve their livelihoods and earn a profit in Nkoroi Village, Kajiado North.

What is Mother Units

“Mother units is a concept borrowed from the mother chicken (kuku), who hatches and takes care of her young before they are set free and she starts laying eggs again,” Mrs Ng’ang’a explains.

The mother unit concept is a component of the WYETU (Women and Youth Economic Transformation Unit) model. In the model, there are other concepts such as households that are the main clients for mother units and raise the birds for meat or eggs.

“The mother unit is our business arm, while the household helps us to attain our vision of rural transformation using agribusiness,” she adds. Jolly Poultry started implementing the mother unit model in 2018 and currently has more than 260 mother units across the country. The mother unit concept defines an entrepreneur in the informal kienyeji chicken value chain. The unit’s business is raising chicks from day one to 21 days and selling them.

Jolly Poultry

At Jolly Poultry, there are only two chicken coops. One is used to raise day-old chicks for sale and another as a model poultry house for training would-be farmers. The latter is also used to get eggs and meat for home consumption, with the surplus being sold.

The mother units

The mother units

Despite the negative effects of the coronavirus on individuals and businesses, including the poultry sub-sector, for Jolly Poultry, the pandemic has been a cloud with a silver lining. It has given her an opportunity to expand the mother units even as she faces other challenges.

From humble beginnings, the poultry farmer has developed thriving mother units that have empowered households, giving financial independence and stability to their lives, one bird at a time

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) recognises women’s economic empowerment as being “critical to achieving gender equality and sustainable development”. With the lockdowns and travel restrictions imposed at the start of Covid-19 pandemic, women found themselves with a lot of time. They needed something to keep them busy, and Jolly Poultry grabbed the chance.

The WYETU’s mantra is to transform livelihoods through agribusiness. “We have been importing chicks. However, at the start of Covid-19, I sold all I had in stock due to increased demand. I saw an opportunity to strengthen the mother units. My vision is to replicate what I do in the mother units and improve women and youth households through poultry rearing,” Mrs Ng’ang’a says. Poultry farming requires little investment compared to keeping dairy cows. It also gives good returns in a short time.

“Households having more than 2,500 birds can make a profit of about Ksh100,000 per month with good agricultural practices,” she adds. “We are slowly discovering how we can use Kuroiler birds as an agent of change in ‘livelihood transformation’ of women and youth.” The farm sells one and two-day-old chicks and three-week-old chicks to the mother units.

The price, Mrs Ng’ang’a explains, depends on the transportation cost and exchange rates, among other things. Mother units are designed to build up farm entrepreneurs. It’s the centre space for the distribution of day old chicks and aggregation for off-taking mature birds for the market.

There are three levels of mother units. The progressive one consistently handles a minimum of 800 day-old chicks to a maximum of 2,500 chicks a month. They have a capacity to work with at least eight households who rear 100 birds to maturity every month.

Upcoming mother units handle 300 day-old chicks to a maximum of 800 chicks and deal with a minimum of eight households rearing 50 to 100 birds to maturity. Advanced mother units handle a minimum of 2,500 chicks to a maximum of 6,000 chicks.

The mother unit picks birds from the farm, raises them for three weeks and sell them to household farmers at Ksh250 and they are encouraged to raise them for meat or eggs to complete the value chain.

The Imports

Jolly Poultry imports 10,000 to 32,000 Kuroiler F1 species from farms with parent stock in India or Tanzania.Per consignment, Jolly poultry imports from a minimum of 5000 day old chick upto a maximum of 32,000. Ideally, they will often import 22,000 day old chicks which is easier to handle.

“We import chicks three times a month but stay flexible to allow the market forces to dictate. But we are more active from February to November,” Mrs Ng’ang’a adds. The mother unit concept helps to give business clarity for production planning. The poultry farm has been importing chicks from India and Tanzania. However, since Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the airspace, they have been sourcing more from Tanzania.

“I prefer the Kuroiler F1 type, which I charge for between Ksh110 and Ksh150. A week-old chick costs Ksh160. Two and three-week-old chicks fetch Ksh200 and Ksh250, respectively,” she says.

So how did she build the venture?

“I started in 2014, when I bought 1,000 day-old birds at Ksh65 each from the National Animal Resource Centre in Entebbe, Uganda. It was when the Kuroiler was first introduced in Africa.

“We transported them by bus, resulting in a high mortality. But didn’t give up. We continued with the business until the availability, quality, and government regulations became a challenge,” says the poultry farmer, who had earlier made a fortune from quail farming being amongst the first pioneers in theat business. She then stopped importing and closed the business.

A layers and broilers’ production unit set up to plug in the income gap, also collapsed.

“This was too stressful. I think it was because of lack of experience but it was a total failure. The eggs price was too low to even feed the chickens. The broiler demand was high when our birds were not ready and would drop when they matured. Feeding, too, was expensive and quality was a challenge,” she recalls.

She would then join the University of Nairobi in September 2015 and later, Hohenheim University in Germany in 2018 to pursue her PhD in Dry Land Resource Management, through a DAAD scholarship.

Return to chicken farming

In 2016, she made a comeback and imported 3000 day old chicks from India. She also sourced for chicks from Uganda.

“That is how I decided to venture into the business of importing chicks,” she reveals adding that she would later shift to Tanzania because of the high costs involved. She stopped busines briefly to focus on her studies but , used her stint at the institution as a learning curve.

“I spent a lot of time visiting farms and learning new technologies. Every time I visited a farm, I would share the experience on my Facebook page and my classmates challenged ittle investment compared to keeping dairy cows. It also gives good returns in a short time me to do a presentation on the same”

Holiday dinner

“During holidays, I decided to start a dinner meeting where I would transfer the knowledge I had acquired to agribusiness enterprenuers.This included training in beef production, vertical farming, and strawberry farming among others. I would charge Ksh3,000 inclusive of dinner for the training per person,” recalls Mrs Ng’ang’a. Uganda had ruined the Kenyan farmer’s perception of Kuroiler birds due to a lot of inbreeding in and I was also trying to change that,” she adds.

In October 2018,the poultry farmer organised a luncheon and invited other poultry farmers to meet and interact with the Keggfarm Chief Executive Officer Mr Vipin Manltra.This was the beginning of the Kenya Kuroiler Platform that desires to see the farmers get the real benefit of the pure Kuroiler birds, she adds. She would bounce back in 2018 after a meeting with the Keggfarm CEO in October that saw her start importing batches of 3000 and 5000 chicks from India until Covid-19 pandemic struck.

Covid-19 effects

Mrs Ng’ang’as nightmare now is the logistical challenges arising from border closures due to Covid-19, exchange rate fluctuations, and high cost of feeds.

“Covid-19 led to the closure of borders and our drivers needed certificates to access neighbouring countries, which was an additional expense,” she notes.

“Feeds are expensive with a 70kg bag of chick mash ranging from Kshs2, 500 to Kshs3,350, which the birds can consume in two days. We encourage and train household poultry farmers on how to make their own feeds from maize germ, soya meal, sunflower and cotton cakes, and fish meal,” she says. Another problem for importers and farmers is that Kenya lags behind in Kuroiler production and there is no funding. “Kuroiler hatching is an expensive venture and you cannot bring in the chickens if you don’t have a ready market,” Mrs Ng’ang’a notes.

What next?

To mitigate the low kuroiler production, Jolly Poultry plans to start hatching them locally. “We hope to get the parent stock from India and raise it to six months. And plan to build the facility in Kajiado County”

“We are also piloting a new idea, the ‘father units’, where coordinators earn their money from the chicken distributed to mother units that they acquire through marketing. For example, if a mother unit has 500 orders, the coordinator who supplies the birds earns Ksh10 per bird. They only earn from the chicken distributed to the mother units. And our target is raise 1,000 mother units,” she explains.

Her word of advice to farmers interested in starting poultry farming ventures. “Do not count your profits based on the first month’s experience. Give yourself time to learn from mistakes. Farmers must remain creative and innovative.”

ALSO READ ABOUT: kiambu-poultry-farmers-cooperative-the-power-of-a-visionary-group